When Visitors Pay It Forward: The Role of Tourism Taxes in Protecting Place

In 2018, ‘overtourism’ was shortlisted as ‘word of the year’ after being added to the Oxford English Dictionary. Overtourism, or too many visitors going to popular places, harming the environment and negatively impacting residents' lives, had officially entered the public discourse.

2019 was subsequently named the “year of the tourism tax" by a United Nations White Paper, Tourism Tax by Design. Of the 30 EU countries studied, all but nine had implemented tourism taxes since 2000. By the time the pandemic hit, a storm was brewing in destination cities and towns across the globe; the time to transition from destination marketing to destination management had arrived.

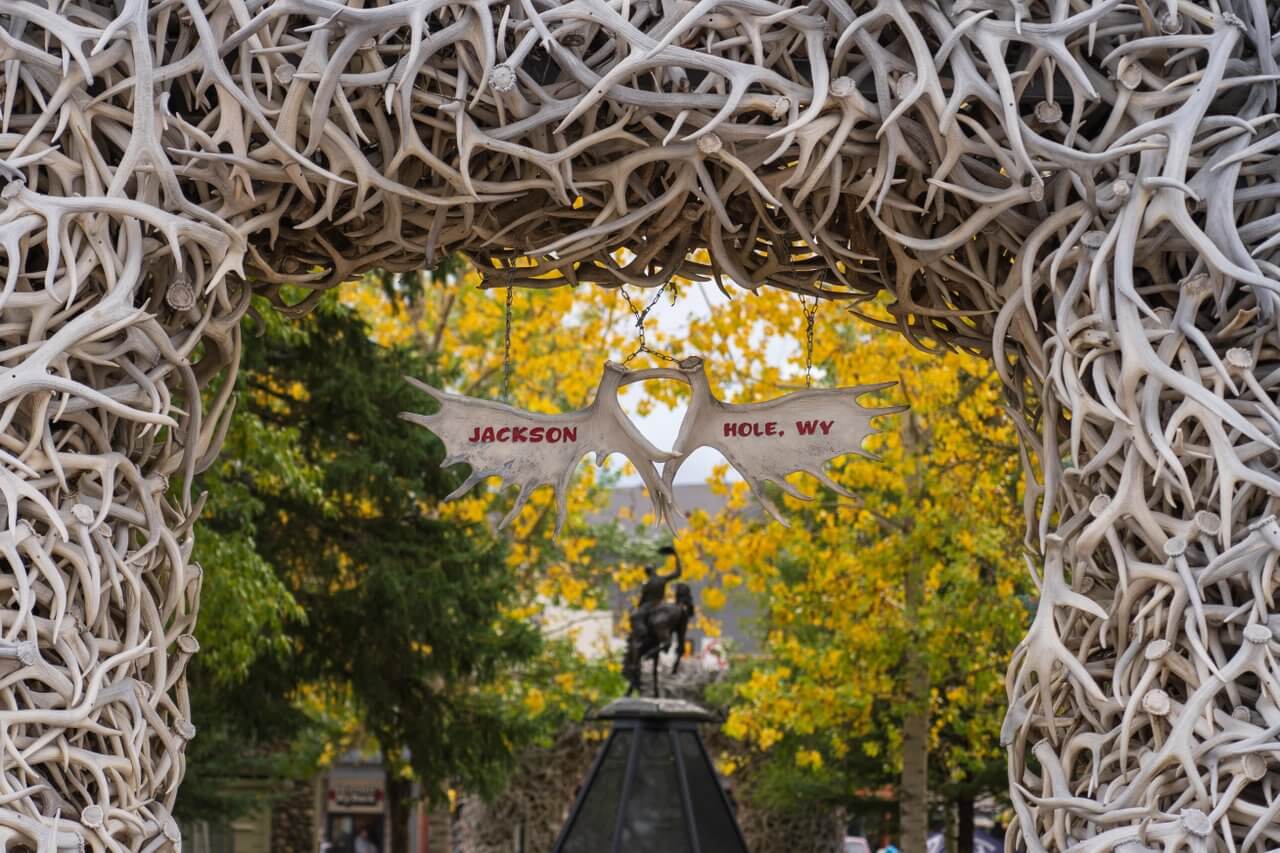

Jackson Hole was no exception—gone were the days of simply driving visitor traffic and not worrying about the impact.

Jackson Hole’s Tourism Board as a Case Study

“We’ve come a heck of a long way,” recalls local business owner and Wyoming state senator, Mike Gierau, “from the old five motel owners and an ad guy on our travel and tourism board and just deciding, ‘are we going to buy an ad in the New York Times or are we going to buy an ad in the in the San Francisco paper or are we going to put billboards like we used to do up on the way up to Aspen and Vail that say, ‘If you were in Jackson, you’d be skiing by now?’” Gierau adds, “Today it’s matured to a level that is actually incredibly sophisticated.”

The sophistication lies not only in creating marketing messaging that sets realistic visitor expectations and promotes sustainable visitor behaviors, but also in reinvesting tourism tax revenue into the community and its resources. Last year, Teton County collected over $6 million in lodging taxes. Forty percent of that tax directly funds the town and county government to address the impacts of high visitation. Of the other 60%, managed by the Jackson Hole Travel and Tourism Board (JHTTB), $2.1 million was allocated toward ‘regenerative’ activities, including community events, partnerships, wayfinding and orientation media, tourism infrastructure, and natural resource protection.

Though the JHTTB has been reinvesting funds back into the community since 2011 when the lodging tax was first put in place, the strategy was codified in the 2023 Sustainable Destination Management Plan (SDMP). The SDMP was developed as a collaborative effort between the JHTTB, local government, land management agencies, stakeholders, and community members to guide Teton County toward becoming a more sustainable and regenerative destination over the next five years. According to the JHTTB’s Annual Report, “sustainable destinations boast healthy economies, proactive infrastructure and public facilities, strong community ties, ecosystem protection, and respectful bonds between visitors and locals working toward shared goals. Destinations that develop plans to harness the power of tourism see healthier communities and attract travelers who support the economy and nourish the environment.”

Tourism at Work in Other Communities

Across the globe, regenerative taxes are experiencing a surge in popularity as a unique type of tourism tax that invests in regenerative agendas, including cultural and heritage preservation, development of tourism infrastructure, and protection of natural resources. Sustainable destination management is only possible when there is an emphasis on regeneration. Regenerative tourism fosters pride and strengthens community identity. It not only benefits locals but also offers tourists a more genuine and meaningful experience.

Recipients of Teton County’s lodging tax represent a wide array of community life, helping to strengthen Jackson’s shared identity as a patchwork of diverse interests and values. Past funding support has ranged from partnerships for trail ambassador programs, to Nordic trail grooming and mapping, to app-based downtown historic walking tours, and to events such as to Turkey Trots, to the Rendezvous Music Festival, to airport shuttles, to Old West Days, to the Jackson Native Art Market, and to Junior Ranger Days.

Jackson has been strategic in placing those investments and, finding nonprofits that can leverage the investment through partnership, allowing the investment to go further. Nancy Leon, founder of JH Nordic, a nonprofit that supports winter recreation in Jackson Hole, Teton Valley, and Grand Teton National Park, seized the opportunity early on to build a community asset from the infusion of lodging tax dollars. JH Nordic identified miles of potential winter trails that were an untapped visitor resource, which would also make an unparalleled local amenity. The organization partnered with the NPS and the Grand Teton National Park Foundation. Leon recalled, “A four-way partnership enabled that to happen, so there’s an ecosystem that was built through partnership. And that’s really powerful. And that work really helps the locals and it really helps out Jackson Hole as a place. You can come in the winter and you don’t have to be a steep and deep skier.”

Tourism Preserving Community Culture

Tourism is often criticized for its impact on heritage, as hospitality amenities frequently replace historic places. However, in Teton County, the lodging tax has also been used to promote storytelling and placemaking, reversing the traditional narrative on heritage and tourism. The Jackson Hole History Museum has used lodging tax funds to support exhibitions and events that preserve the community’s sense of identity through sharing its collective history. Morgan Jaouen, the Museum’s Executive Director, shared, “For over 11,000 years, this valley has been shaped by Indigenous peoples, settlers, ranchers, entrepreneurs, conservationists, recreationists, and many others. Much of our recent history revolves around the tourism industry and the conservation movement. We want to engage visitors with these defining stories; inspiring everyone to both enjoy and care for this special place.”

Jackson Hole isn’t immune to tourism pressures, but with careful management and reinvestment in what gives the community its character, it can avoid the ravages of overtourism. And, while opinions may vary about how to retain that character, as Mike Gierau points out, “as a community, we’re very used to having a good, healthy, robust dialogue about this, and it’s a constant discussion. It’s not something that just comes up every now and again. It is a living, breathing thing.”